Hello!

Let’s continue talking about the German grammatical cases… It’s a little boring (I know)… I was trying to delay my studies about it…. buuuut, it is important to know… so, here we go!

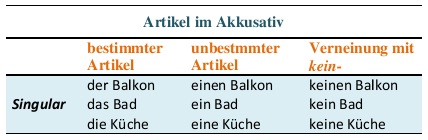

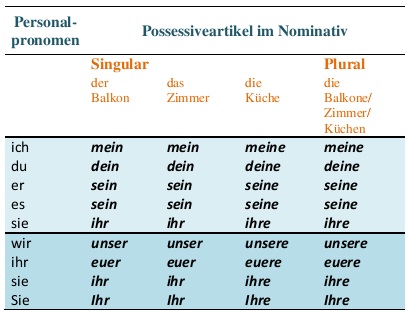

Today we will learn about the accusative case (,,der Akkusativ“). The accusative case is known as the direct object of a sentence. The direct object is the immediate recipient of an action or event. In other words, the direct object functions as the receiver of the action of a transitive verb. In German you can tell that a noun is in the accusative case by the masculine article, which changes from ,,der/ein” to ,,den/einen“. You don’t need to worry about the feminine, neuter or plural, because they don’t change in the accusative case! Click here for more informations.

You can test for a transitive verb by saying it without an object. If it sounds odd, and seems to need an object to sound right, then it is probably a transitive verb. Take a look at the following examples (Both of these phrases answer the implied question “what?”):

,,Ich habe…” (I have…) ⇨ What do you have?

,,Er kaufte…” (He bought…) ⇨ What did he buy?

On the other hand if you do this with an intransitive verb, such as “to sleep”, “to die”, or “to wait”, no direct object completion is needed, because you can’t “sleep”, “die” or “wait” something. Some verbs can be either transitive or intransitive, but the key is to remember that if you have a direct object, you’ll have the accusative case in German.

The question word in the accusative is ,,wen” (whom):

,,Wen hast du gestern gesehen?” (Whom did you see yesterday?)

ACCUSATIVE TIME EXPRESSIONS

The accusative is used in some standard time and distance expressions.

,,Das Hotel liegt einen Kilometer von hier.” (The hotel lies a kilometer from here.)

,,Er verbrachte einen Monat in Paris.” (He spent a month in Paris.)

,,Aschenputtel und der Prinz haben die ganze Nacht getanzt.” (Cinderella and the prince danced all night.)

ACCUSATIVE PREPOSITIONS

Some German prepositions are governed by the accusative case. There are two kinds of accusative prepositions: those that are always accusative and never anything else and certain “two-way” prepositions that can be either accusative or dative (depending on how they are used).

Here is a list of the accusative-only prepositions.

| Accusative Prepositions |

| Deutsch |

Englisch |

| bis |

until, to, by |

| durch |

through, by |

| entlang |

along, down |

| für |

for |

| gegen |

against, for |

| ohne |

without |

| um |

around, for; at (time) |

NOTES!

- The accusative preposition ,,entlang“, unlike the others, usually goes after its object.

- The German preposition ,,bis” is technically an accusative preposition, but it is almost always used with a second preposition (,,bis zu“, ,,bis auf“, etc.) in a different case, or without an article (,,bis April“, ,,bis Montag“, ,,bis Bonn“).

The meaning of a two-way preposition often depends on whether it is used with the accusative or dative case.

Two-Way Prepositions

Accusative/Dative |

| Deutsch |

Englisch |

| an |

at, on, to |

| auf |

at, to, on, upon |

| hinter |

behind |

| in |

in, into |

| neben |

beside, near, next to |

| über |

about, above, across, over |

| unter |

under, among |

| vor |

in front of, before; ago (time) |

| zwischen |

between |

The basic rule for determining whether a two-way preposition should have an object in the accusative or dative case is motion versus location. The following rule applies only to the so-called “two-way” or “dual” prepositions in German.

- The accusative occurs when there is motion towards something or to a specific location (,,wohin?“, where to?).

,,Wir gehen ins Kino.” (ins = in das) (We’re going to the movies/cinema.)

,,Legen Sie das Buch auf den Tisch.” (Put/Lay the book on the table.)

- The dative occurs when there is no motion at all or random motion going nowhere in particular (,,wo?“, where (at)?).

,,Wir sind im Kino.” (im = in dem) (We’re at the movies/cinema.)

,,Das Buch liegt auf dem Tisch.” (The book’s lying on the table.)

Many of these prepositions have another meaning in common everyday idioms and expressions: ,,auf dem Lande” (in the country), ,,um drei Uhr” (at three o’clock), ,,unter uns” (among us), ,,am Mittwoch” (on Wednesday), ,,vor einer Woche” (a week ago), etc. These expressions can be learned as vocabulary without worrying about the grammar involved.

That is what I’ve learned about accusative case today… if I learn something else, I will let you know!!!!

See you!! 😀